What is Knowledge?

For generations, we have pursued a "knowledge-based" curriculum that was developed at a time when access to information was scarce. Today’s digitally connected world offers unlimited, immediate and accurate information to nearly all the world’s questions. As answers to questions we already know provide little, if any, competitive advantage in today’s world it can be argued that education should now focus on stimulating and promoting the discovery of new possibilities.

An undercurrent of change driven by new teaching practices with proven success includes greater focus on functional skills, collaboration, creativity, understanding and evaluation of online data, social and cultural awareness, global connectedness and effective communication. This shift has seen acceptance of the sharing of learning outcomes and a move from ‘covering the curriculum’ to ‘discovering’ it.

‘The fact is that given the challenges we face, education doesn’t need to be reformed - it needs to be transformed. The key to this transformation is not to standardise education, but to personalize it, to build achievement on discovering the individual talents of each child, to put students in an environment where they want to learn and where they can naturally discover their true passions” (Robinson, 2009)

What do you hope to achieve during the 32 weeks of this programme?

During the class session, we will ask you to fill in the form at tinyurl.com/mylearningoutcomes, to summarise your three main learning goals for your Mind Lab journey. Since you might have already heard some good new ideas from others, your hopes may be a bit different than the reasons you originally added to the Post-its.

Jobs that Don’t Exist Yet?

The Mind Lab by Unitec exists because the future is changing. This is the reason for offering the programme that you are currently enrolled on. A truism that is often encountered is that we are educating students for jobs that don't yet exist, and that we don't know what these jobs will be. The first part is fair enough, the second part less so - the Internet is full of lists of future jobs. This is just one example (Frey, 2014).

- Senior Living, e.g Life-Stage Attendants and Aging Specialists

- Future Agriculture, e.g. Molecular Gastronomists and Bio-Hacking Inspectors

- Driverless Everything, e.g. Delivery Dispatchers and Driverless “Ride Experience” Designers

- The Dismantlers, e.g. Government and Education Agency Dismantlers

- Micro-Colleges, e.g. Career Transitionists and School Designers

- Bio-Factories, e.g. Bio-Factory Doctors and Gene Sequencers

- Atmospheric Water Harvesters, e.g. System Architects and Water Supply Transitionists

Knowledge as Justified True Belief

The Greek word, ‘episteme’, refers to knowledge, and epistemology tries to identify the essential, defining components of knowledge. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP, 2017a) is one of the sources explaining that knowledge is a justified true belief. That source itself is an interesting one from the knowledge perspective since SEP has been designed so that each entry is maintained and kept up-to-date by an expert or group of experts in the field. All entries and substantive updates are refereed by the members of a distinguished Editorial Board before they are made public.

Social Epistemology in the Internet Era

Until recently, epistemology - the study of knowledge and justified belief - was heavily individualistic in focus. The emphasis was on evaluating individuals apart from their social environment. The result is a distorted picture of the human situation, which is largely shaped by social relationships and institutions. Social epistemology seeks to redress this imbalance by investigating the effects of social interactions and social systems. (SEP b, 2017)

The Internet has given rise to online collaborative tools for aggregating information disseminated among a large number of individuals who may not be experts on the topics they treat. A notable example is the free online encyclopedia Wikipedia. Wikipedia’s goal of making existing knowledge widely available is distinctively epistemic, so the question many want to raise is how well it can achieve its aim.

Can You Trust Wikipedia?

The question is of great practical importance, for on the one hand Wikipedia is one of the most widely used sources of information, while on the other hand there are pressing concerns about its epistemic quality. Since anyone can contribute anonymously to Wikipedia, there is no guarantee that writers of an entry are experts (or even know anything) about the topic at hand. Indeed, Wikipedia’s culture is sometimes said to openly deter experts from contributing. In addition, since contributions are anonymous or at any rate not easily trackable, contributors may vandalize pages or actively try to deceive readers by spreading false information.

Like most people, you might use Wikipedia only to satisfy your curiosity or as a mere starting point for in-depth research, and even according to SEP (2017b) Wikipedia may well be reliable enough for these purposes. Worries about vandalism and deception are in part alleviated by the fact that Wikipedia has several built-in features (such as disclaimers and discussion pages) to help readers assess the reliability of an entry. We hope you learn to use and check those functions.

Fallis (2011) has pointed out that reliability is not the only virtue that matters when it comes to sources of information. In addition, we care about power (how much information can be acquired from a source), speed (how fast the information can be acquired) and fecundity (how many people have access to the source). Wikipedia may well be less reliable than traditional encyclopedias but it is certainly a more powerful, speedy and fecund source of information.

And if you see something that is not true in Wikipedia, shouldn’t you go and suggest a change? .

Knowledge in Cultures

Of course 'Western' views of epistemology are not the only perspectives. “While Western science and education tend to emphasise compartmentalized knowledge which is often de-contextualized and taught in the detached setting of a classroom or laboratory, indigenous people have traditionally acquired their knowledge through direct experience in the natural world. For them, the particulars come to be understood in relation to the whole, and the ‘laws’ are continually tested in the context of everyday survival.” (Barnhardt & Kawagley, 2005).

Knowledge has a genesis, it has a place of origin... Knowledge is shaped by what culture believes are “best practices.” It is not something that is reinvented every generation. This knowledge-belief structure cannot possibly have a specific answer to how one approaches technology, for instance, but it sets the tone for how one handles technological influence and places it within a structure of values, priorities, and spiritual beliefs. (Meyer, 2001). .

Purpose of Education

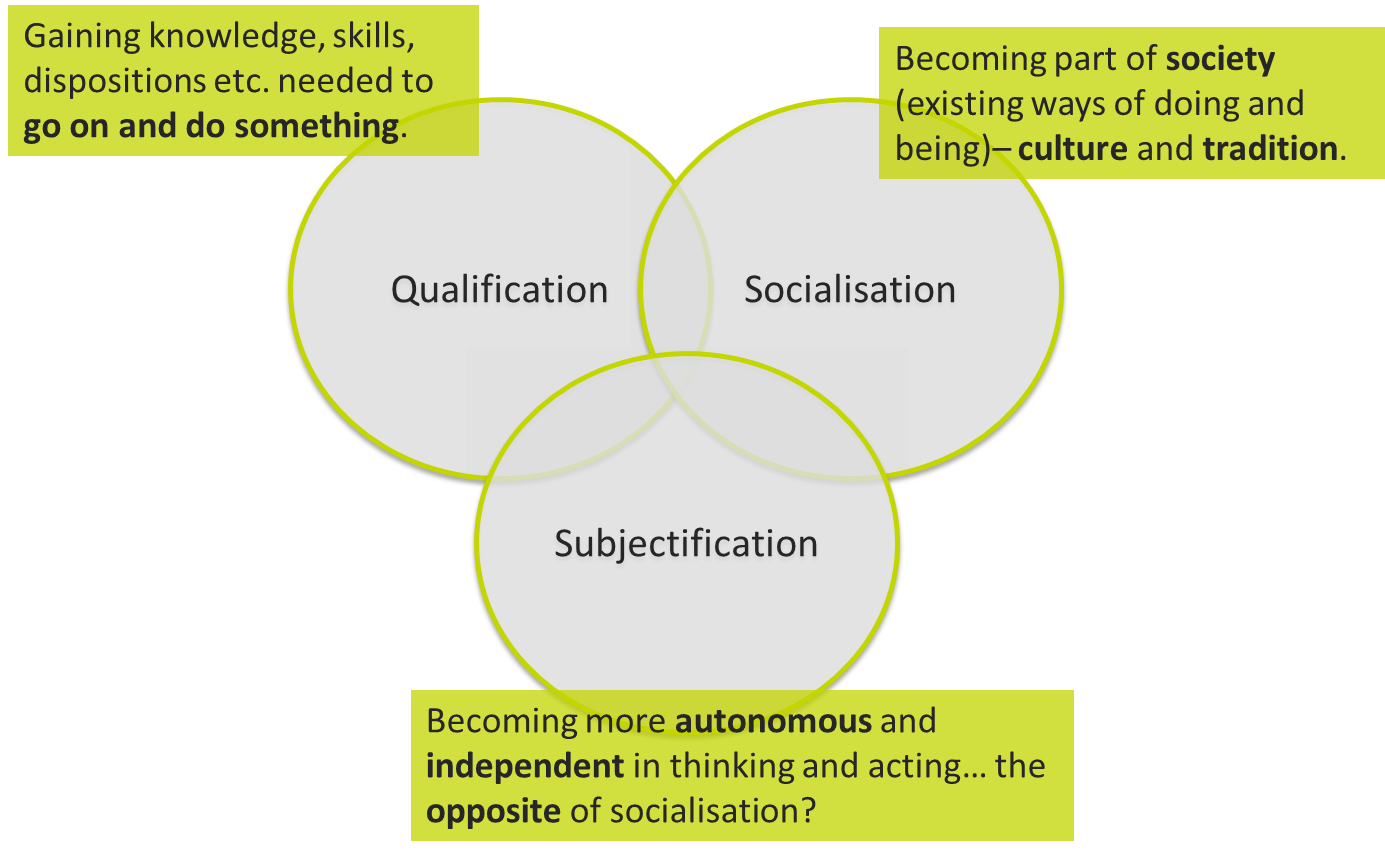

Biesta (2005) helps us to a wider view of education by focusing on the question of purpose – putting the ‘why’ of education before the ‘how’. He suggests three broad domains of educational purpose, illustrated in the diagram below by Phillipson (2014).

The Purpose of Education Today

One of the commonly stated ideas in education today is that we are no longer training students for specific jobs or careers. Rather, we need to provide them with the necessary skills to adapt to (and indeed create) future opportunities. “Our job as teachers and parents is not to prepare students for something; our job is to help students prepare themselves for anything.” (Juliani, n.d.).

Goals for Maori Education

In February 2001 the first Hui Taumata Mātauranga provided a framework for considering Māori aspirations for education. It resulted in 107 recommendations based around the family, Māori language and custom, quality in education, Māori participation in the education sector and the purpose of education. There was also wide agreement about three goals for Māori education:

- to live as Māori

- to actively participate as citizens of the world

- to enjoy good health and a high standard of living

(Durie, 2004).

References

Barnhardt, R. & Kawagley, A.(2005). Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Alaska Native Ways of Knowing, Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 36(1), 8–23.

Biesta, G. (2015). What is education for? On good education, teacher judgement, and educational professionalism. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 75-87.

Durie, M. (2004). Māori achievement: Anticipating the learning environment. Hui Taumata lV: Increasing Success for rangatahi in education. Insight, reflection and learning. Palmerston North, NZ: Massey University.

Fallis, D. (2011). “Wikipistemology”, in Goldman and Whitcomb 2011: 297–313.

Frey, T. (2014) 162 Future Jobs: Preparing for Jobs that Don’t Yet Exist. DaVinci Institute – Futurist Speaker. Retrieved from http://www.futuristspeaker.com/business-trends/162-future-jobs-preparing-for-jobs-that-dont-yet-exist/

Juliani, A.J. (n.d.). What I’m Working On Right Now. Retrieved from http://ajjuliani.com

Meyer, M. A. (2001). Our own liberation: Reflections on Hawaiian epistemology. The Contemporary Pacific, 13(1), 124-148.

Phillipson, N. (2014). Biesta, the Trivium and the unavoidable responsibility of teaching. 21st Century Learners. Retrieved from http://21stcenturylearners.org.uk/?p=492

Robinson, K. (2009). The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything. Penguin.

SEP. (2017a). Epistemology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7th of November 2017 from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology/#SEP

SEP. (2017b). Social Epistemology. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7th of November 2017 from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-so...

No comments:

Post a Comment